What Changes

There was a family I loved—brilliant mom, sensitive dad, lovely boy—and once they stopped by unannounced for a visit to the tiny studio apartment where our family of four lived like puppies in a cardboard box. Our “spirited” three-year-old, Milo, hit the lovely boy, not all that unusual an occurrence from our perspective. I apologized profusely, and Milo peeped out a meager “I’m sorry,” but the brilliant mom changed in that moment. Her body language became formal, each motion clipped and deliberate. She was furious with Milo, her body shot through with the instinct to protect her son. She couldn’t look at me.

“Why did Milo do a bad thing?” the other boy kept asking in a querulous little voice like a character in a David Lynch film. His mom’s answers moved from generous—“Milo’s still learning”—to downright hostile—“Sometimes people just aren’t good.” They left promptly, without any see-you-soons.

I was obsessed with how I could have handled things differently because I thought our friendship was strong enough to handle the indiscretions of toddlers. I was wrong, and I hate being wrong.

Many friendships do not survive the process of having kids. Pregnant ladies are not the life of any party, and the crib versus co-sleeping quandary is not all that interesting to the childless. Worse is when you have remained friends despite (or perhaps as a result of) your pregnancies and then the friendship is tested by your deranged offspring. But the truth is that you change profoundly after giving birth, and friendships cannot always weather it.

How did having children change me? So much for my perpetual smile and tight abs. Gone are the international wilderness adventures on a whim. I cannot even think about regular exercise or extended personal grooming. I have lost friends and keys and important documents and, let’s just be honest, my mind.

My priorities shifted from career advancement to not inadvertently exposing my whole breast in public (except for when breastfeeding). My fears morphed from shark attacks to bathtub drowning. My passions changed from slam poetry to grocery lists organized by aisle.

What else changed? My wardrobe. My routines. The speed at which I drive. Social calendar. Bank account. The interior decoration at my residence. Sleeping, eating, and drinking habits. Tolerance for pain, strong smells, and messes. Use of prescription medication and/or illegal substances.

And yet I look back on myself before my children were born with actual scorn. How does that work? How can we lose everything and still gain?

I think of my friend from high school, JT. He was kicked out of our prestigious public school because his GPA skewed the average so harshly downward. He then went to an “underperforming” alternative academy. When I was in college, I heard the news that JT had been arrested for armed robbery and was in prison. We didn’t keep in touch but reconnected after he got out. We went to Mardi Gras in New Orleans together and mutually supported one another’s devil-may-care approach to partying there.

Fast-forward ten years—we both had toddler sons and we planned to meet at my childhood home, with our boys in tow.

JT came through the door smiling widely like he used to. My mom’s bear-cub-sized dogs jumped and barked, which made JT’s son cry. JT started to move to hug me, but instead knelt to comfort his son. I noticed the paisley print of the diaper bag slung over his shoulder. JT’s son bee-lined to my mom’s overpopulated Christmas tree and began breaking heirloom ornaments. We swept up the shards of broken glass before Grandma could see them, like we did with broken beer bottles in the past. Our initial conversation was punctuated by warnings and answers to inane questions posed by our kids. A lot of things we wanted to say we couldn’t say. What happened? Are you happy? Is your kid as impossible as mine? How’s your spouse? Are you bored? Do you miss having the freedom to stay out all night reveling with strangers? Our toddlers tussled over toys and stuffed Cheerios into their orifices. They crawled all over each other like newborn rodents.

“Hands, Daddy,” JT’s son said, holding out his sticky palms for JT to wipe clean, like a prince to his attendant. The look that passed between father and son was pure and true. I moved involuntarily toward Milo to see if he needed something, and he scooted away from me. I thought for the millionth time how things might be different if I were to have had an adoring, passive daughter like I had been, or were my temperament to match that of my child. A tower of blocks toppled loudly and Milo squealed with laughter. Ha ha. How would I ever find the stamina to watch this same scene again and again, to pretend to be surprised and delighted by gravity? I was tired. Play dates inevitably ended in crying and I wished we could just skip to that part, or better yet, past it, to bedtime.

JT seemed plenty calm and present. I wondered if he were stoned, hoped he was, suspected he wasn’t. Probably he didn’t mess around anymore. You find other ways to relax and settle your mind. Maybe with plastic keys, light up frogs, squishy bath books. The detritus of child rearing stressed me out, but JT seemed positively peaceful.

“It’s a trip,” JT said, or maybe we both thought it, and I just imagined him saying it. “When I hear the toilet flush in the middle of the night, I’m like YES!” he said. I nodded. I thought he meant that nighttime toilet training is hard won. Milo’s diaper was sticking out over the top of his pants, making his bottom appear larger than it really was. There was snot pooled in that indentation between Milo’s nose and his lips; I wondered about the scientific name of that part of us.

JT was still holding his overflowing paisley diaper bag and I wondered if it was too late to welcome him to put it down.

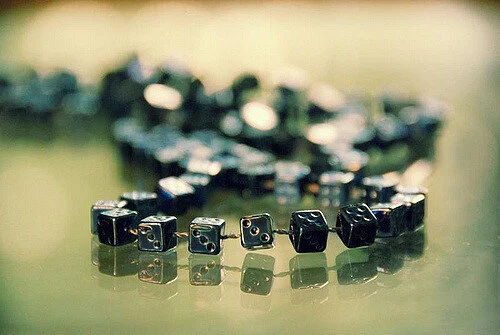

After we said goodbye, my thoughts kept boomeranging back to the best Mardi Gras beads I ever got, “earned” by flashing a Japanese businessman with JT by my side. Huge Carmen Miranda fruit beads, plastic bananas and pineapples and oranges and apples and pears, larger than life, scratchy on the back of my neck, a badge of honor on Bourbon Street. JT protected me from men who tried to touch me when I lifted up my gold sequined top. He pushed their hands away, I think. I could only remember the seething masses and the bigger and bigger beads I collected as the drunk became drunker, culminating in those fruits, my crowning achievement.

Now the Mardi Gras beads languished in my basement next to the Easter decorations. Now we were grownups with mortgages; we were everything we once avoided.

JT wasn’t as I remembered, cradling his son: vulnerable, accessible, soft around the edges. Parenthood knocked me off my overachieving pedestal—Ivy League grad, stellar grades, awards won—and placed JT, a convicted felon, deservedly on one. To be needed, it unraveled me, and it bolstered JT. Our toddlers cared not one bit about our reputations or our GPAs. To be a successful parent, it dawned on me, all you needed to be was present, loving, and engaged.

Tides and friendships shift. You continue to wipe sticky hands and kiss wet eyelids. You move on.

Mardi Gras beads by Faungg / Flickr Creative Commons